We’ve all been there. Blankly staring at a screen hoping that your speech therapy goals would write themselves, and the IEP would be complete. After the long process of an assessment, it feels like you’re at the summit only to find there’s another mountain to climb. 🏔

We’ve got you! Keep reading if you want tips on how to create smart goals!

How to Write SMART Goals to Help Your Students and Make your IEP Goals as Clear as Possible

This post will help guide you on a path to write SMART goals that really help your students. My goal is to help make your goal writing a little easier. The decision process is hard to nail down and something you learn on the job, but I’m hoping this guide will give you some good ideas!

Getting Started with Speech Therapy Goals

Let’s start at the beginning with a little review of what can prepare you for writing really solid speech therapy goals.

1. A complete assessment that included formal and informal testing

2. Input from the student, teachers, staff members, and family members

3. Data from your sessions (if applicable)

4. Your student’s strengths and the foundation you’re going to build on

5. An understanding of your student’s challenges and where they are struggling in the school environment

If you’re an SLP Now member, you have access to the paperwork binder that includes assessment, treatment plan ideas, and factors to consider that can help shape your speech therapy goals. There are also lots of quick informal assessments to use for baseline and probe data!

S.M.A.R.T. Goals

We all know our speech therapy goals need to be SMART, but how do you get from your assessment results to goal areas to target? We’ll go through a couple of different treatment areas to cover our bases.

S – Specific: Is your goal specific? Did you talk about the setting? Are you putting too many things in one goal?

M – Measurable: Can you measure this goal with data? Consider a rubric for some of those harder-to-measure speech therapy goals.

A – Attainable: Is this goal attainable in a year for this particular student? Goals are individual, make sure it’s feasible for this student.

R – Realistic: Is this goal something that will generalize to the classroom/school environment and help the student succeed at school? Have you considered the whole EBP triangle with research, clinical judgment, and information from the student and their family?

T- Timely: Can the student achieve the speech therapy goal in the amount of service time you are recommending for the IEP?

Start with our Speech Therapy IEP Goal Bank

If you’re wondering where you should start, the SLP Now Goal Bank is full of speech therapy goal ideas that can help you create individualized speech therapy goals based on your students’ speech and language strengths and needs.

The goal bank includes AAC goals, fluency goals, social language goals, receptive language goals, expressive language goals, articulation goals, and more! Definitely head to the SLP Now Goal Bank to brainstorm IEP goals and objectives for your speech therapy IEP goals.

Tips for Speech Therapy Goals

1. Goals must be educationally relevant in the school setting.

Goals do not have to be based on developmental norms. To be aligned with IDEA, you have to find out the educational impact of the child’s speech errors and select your goals after that process (Ireland & Conrad, 2016).

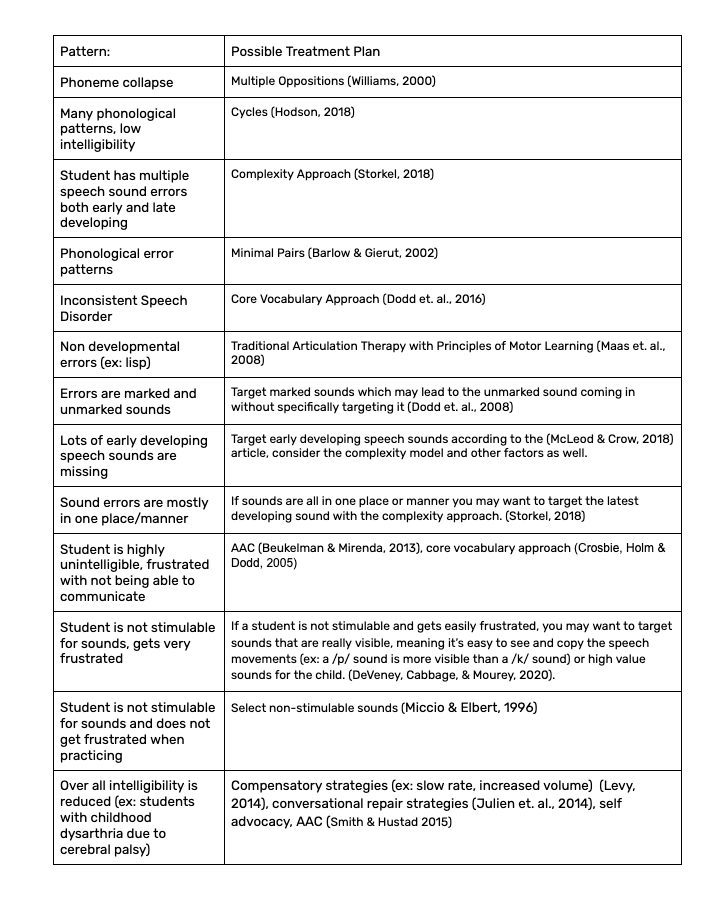

2. Look for patterns.

Do you see articulation errors, phonological patterns, apraxia, inconsistent speech disorder? If your student is bilingual, don’t forget to cross-check the student’s native language!

3. Select a treatment plan.

Sometimes it’s easier to select your treatment plan before you write your goals. That way your goals and treatment plan are nicely aligned. I’m a big fan of the complexity approach!

4. Keep phonological awareness in mind.

Make sure you think about phonological awareness skills as well, especially if the student is writing their error the way they say it. Students with speech sound errors are more likely to have difficulty reading and writing (Cabbage et. al., 2018).

5. Vary your target selection and individualize.

Map out the student’s pattern of errors on a place, manner, voice chart. Make sure that your targets are varied. You might pick one marked sound, one early developing sound, one sound that is relevant to the child’s life, and one sound that is frequently occurring. Choosing targets from different classes is also a good way to make sure you have well-rounded goals.

6. For childhood apraxia of speech.

We love Edyth Strand as a resource. Treatment for childhood apraxia of speech focuses on movement, not specific sounds. Goals should allow for use of an EBP based treatment plan like (Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing) DTTC (Strand, 2020). A goal for syllable shapes (e.g., CV, CVC, CVCV) is one example of a goal that is appropriate for apraxia. Don’t forget to consider AAC!

Whew! That was a lot. Thanks for hanging in there. Check out these related posts on speech sound disorder treatment if that’s your next step in the process!

– A Review of Articulation Approaches

– Tips for Treatment of Childhood Apraxia of Speech

– Where to Start with Phonological Awareness

– How to Implement the Complexity Approac

– How to Implement the Cylces Approach

– Target Selection Considerations for Speech Sound Disorder Intervention in Schools

Tips for Language Goals for Speech Therapy IEPs

Zeroing in on your student’s strengths and challenges can really narrow down where to go with language goals. Look for patterns and what the ROOT of the challenge is. In order to be educationally relevant, your goals need to target skills that will help the child’s ability to access curriculum and participate in the school environment. If your goals aren’t generalizing outside of the speech room, we’ve got some ideas to help!

Make sure to take baseline/probe data in order to be in the student’s sweet spot for learning. Including visuals and varying your prompting can also give you clues about a student’s learning potential. A goal that is either too hard or too easy will not lead to the optimal amount of progress for a student.

1. Work on executive functioning.

Consult with other IEP team members (like the psychologist and special education teacher). Talk about executive functioning challenges you both see. You want to be working on strategies that will generalize into the classroom (Kamhi 2014). For example: Work on using describing words to talk about new concepts instead of memorizing a set of new words, or work on embedded narrative skills like story grammar rather than working on sequencing separately. Working on these types of skills will help executive functioning skills like working memory and planning. It is within your scope of practice to work on executive functioning in the school setting (Ward & Jacobsen, 2014), you probably do already!

2. Consider social-emotional needs.

Consider any factors related to social-emotional aspects (Kirch et. al., 2020).

Are they able to get their daily needs met? Can they talk about how they are feeling? Can they tell a peer a story or joke?

If this is a need, it needs to be a goal.

3. Consider the Common Core.

Look through Common Core State Standards and find where your student isn’t able to participate in the classroom or access academics. I usually start by looking at the speaking and listening and language sections. What sticks out as an area to target?

Some Ideas

– Vocabulary

– Grammar

– Language skills like narratives

– Functional Communication

4. Build on student’s strengths.

Focus on what they were able to do and what the next attainable steps are. (Example: they can describe different things that happened in a story but can’t sequence them correctly in their working memory, so you target story grammar to improve working memory and their ability to tell a story. This helps with both academics and with their social relationships).

5. Consider the educational impact.

Prioritize what will help your students succeed academically and participate in the school environment. This puts you in the right mindset to pick their goals as well. Collaboration is always encouraged. I check in with teachers to make sure that the goals make sense for their classroom and would help them. Make sure there is educational impact in order to justify services!

6. Provide additional speech therapy supports.

Do they need other supports for sensory processing during the session and/or are they a gestalt language processor? This may affect the amount of trials, visuals, prompts/cues, the environment, et cetera as you’re formulating your goals.

Tips for Fluency Goals

For fluency and social goals, a great mindset to have is to think of the social model of disability. We aren’t trying to change the person, we’re thinking of ways to support the student and change the environment in order for them to succeed.

Yes, you read that right! Check out this post by Nina Reeves about why we shouldn’t be writing goals for a percentage of fluency. She links to a handout about writing goals for fluency.

First and foremost, we are going to consider the student and what their communication goals are. We want to focus on creating an environment through education/training and levels of support that encourage the student to be confident and comfortable speaking.

Areas to Target

1. Change the environment.

– Education about stuttering (journals)

2. Support the student.

– Thoughts and feelings about stuttering (including acceptance)

– Demonstrate fluency strategies

– Demonstrate awareness of dysfluencies

– Self-advocacy (e.g., decrease avoidance)

Tips for Social Language Goals

Goals for social language/pragmatics are going through quite the shift lately. In following the social model of disability, our thinking has to shift to what WE can change to accommodate the student, not what they can change about themselves. Research points to masking (an autistic person having to change who they are to blend into a neurotypical world) as being very detrimental to their mental health (Beck et. al., 2020). So what can we do about it? Listening to autistic voices is one way of making sure that you are targeting goals that are supporting the student’s environment and their needs, rather than forcing them to mask.

Check out this website made by an autistic SLP/SLT in the UK!

Goals should not be compliance-based.

Goals should support the needs of the student.

Goals should not support masking, unless requested by the student!

Example Goal Areas

1. Student Supports

Support for gestalt language processing

AAC/any form of communication student is comfortable with

Self-advocacy (e.g., for sensory breaks)

Self-regulation skills (e.g., recognizing when they need a break)

Daily living skills (e.g., job training)

Recognizing emotions in themselves and others

2. Supporting the Student in Interactions

Problem-solving

Self-advocacy (e.g., tell the teacher they are listening so they don’t have to make eye contact)

When working on these goals, push-in lessons are ideal to talk to both neurotypical and neurodiverse students. It’s a great way to promote understanding and to talk about the double empathy problem (Mitchell et. al., 2021). Neurodiverse students don’t have difficulty communicating with each other, but neurotypical and neurodiverse relationships can have difficulty understanding each other.

Being present in the classroom is also a great way to know what supports the student needs in that setting and an easy way to model it for classroom teachers.

3. Supporting the Student Academically

Figurative Language

Narrative Language

Story Grammar

Perspectives in books (e.g., character’s perspectives)

Adjust the Setting and Supports

After your goals are set, you can adjust the setting and any types of supports either with the goal (visuals and prompts) or in the school setting with accommodations/supports sections of the IEP. You’ll also make final adjustments to your service delivery model and service minute recommendations.

I hope this post has given you some confidence to justify your goal areas as treatment targets. It takes a lot of time and practice to go from assessment to goals easily. I still call my SLP friends to bounce ideas off of (following FERPA guidelines, of course!).

Give yourself the space to learn and grow.

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Speech sound disorders: Articulation and phonology. https://www.asha.org/practice-portal/clinical-topics/articulation-and-phonology/#collapse_6.

Barlow, J. A., & Gierut, J. A. (2002). Minimal pair approaches to phonological remediation. Seminars in Speech and Language, 23(1), 57–68.

Beck, J. S., Lundwall, R. A., Gabrielsen, T., Cox, J. C., & South, M. (2020). Looking good but feeling bad: “Camouflaging” behaviors and mental health in women with autistic traits. Autism, 24(4), 809–821.

Beukelman, D. & Mirenda, P. (2013). Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting Children & Adults with Complex Communication Needs 4th Edition. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Cabbage, K. L., Farquharson, K., Iuzzini, -Seigel Jenya, Zuk, J., & Hogan, T. P. (2018). Exploring the Overlap Between Dyslexia and Speech Sound Production Deficits. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(4), 774–786.

Crosbie, S., Holm, A., & Dodd, B. (2005). Intervention for children with severe speech disorder: A comparison of two approaches. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 40(4), 467–491.

DeVeney, S. L., Cabbage, K., & Mourey, T. (2020). Target Selection Considerations for Speech Sound Disorder Intervention in Schools. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 5(6), 1722–1734.

Dodd, B., Crosbie, S., Mcintosh, B., Holm, A., Harvey, C., Liddy, M., Fontyne, K., Pinchin, B., & Rigby, H. (2008). The impact of selecting different contrasts in phonological therapy. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 10, 334–345.

Dodd, B., Holm, A., Crosbie, S., & McIntosh, B. (2006). A core vocabulary approach for management of inconsistent speech disorder. Advances in Speech-Language Pathology, 8(3), 220–230.

Gierut, J. A. (1989). Maximal Opposition Approach to Phonological Treatment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54(1), 9–19.

Hodson, B. W. (2018, March 12). Enhancing Phonological Patterns of Young Children With Highly Unintelligible Speech (world) [Review-article]. The ASHA Leader; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Julien, H. M., Finestack, L. H., & Reichle, J. (2019). Requests for Communication Repair Produced by Typically Developing Preschool-Age Children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(6), 1823–1838.

Justice, L. M., & Fey, M. E. (2018, December 31). Evidence-Based Practice in Schools (world) [Review-article]. The ASHA Leader; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Kamhi, A. G. (2014). Improving Clinical Practices for Children With Language and Learning Disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(2), 92–103.

Kerch, C. J., Donovan, C. A., Ernest, J. M., Strichik, T., & Winchester, J. (2020). An Exploration of Language and Social-Emotional Development of Children with and without Disabilities in a Statewide Pre-Kindergarten Program. Education and Treatment of Children, 43(1), 7–19.

Levy, E. S. (2014). Implementing two treatment approaches to childhood dysarthria. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(4), 344–354.

Maas, E., Robin, D. A., Austermann, H. S. N., Freedman, S. E., Wulf, G., Ballard, K. J., & Schmidt, R. A. (2008). Principles of Motor Learning in Treatment of Motor Speech Disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 277–298.

McLeod, S., & Crowe, K. (2018). Children’s Consonant Acquisition in 27 Languages: A Cross-Linguistic Review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(4), 1546–1571.

Miccio, A. W., & Elbert, M. (1996). Enhancing stimulability: A treatment program. Journal of Communication Disorders, 29(4), 335–351.

Mitchell, P., Sheppard, E., & Cassidy, S. (2021). Autism and the double empathy problem: Implications for development and mental health. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 1–18.

Smith, A. L., & Hustad, K. C. (2015). AAC and Early Intervention for Children with Cerebral Palsy: Parent Perceptions and Child Risk Factors. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 31(4), 336–350.

[…] 5 Tips to Write Speech Goals for IEPs from SLP Now […]