This is a guest blog post by Monica, a school-based SLP, all about tips to implement literacy-based therapy for students with SLI.

Where to Start

If you’re looking for where to start with your students that need additional support for literacy-based therapy, this blog post is right up your alley. I’ll be going over how I modify literacy-based therapy for students with specific language impairment/speech-language impairment (SLI).

First, I will go over some recent research really quickly! It’s important to know where these suggestions are coming from.

Pico et al. (2021) just released a meta-analysis of narrative language interventions. This article had the conclusion that “findings from this corpus of studies suggest that measurable and lasting improvements in macrostructure and microstructure elements of narrative production can result from a variety of interventions even when provided in relatively small dosage.” They also found that many different types of interventions were successful including “manualized and/or scripted curriculum, explicit teaching of story grammar, and verbal and visual prompts.” The interventions included children with “diverse learner characteristics”.

My takeaway from this article is that it isn’t HOW we’re using contextualized narrative intervention; it’s that we’re just using it in the first place. This gives me the green light to keep modifying narrative therapy to support my caseload in a way that is individualized for my student’s unique needs. That’s what EBP is all about anyway, right?

I also reviewed two articles specifically studying children with specific language impairment. Both articles outlined methods that did not teach all of the story grammar elements in one lesson.

📕 Gilliam and Gilliam (2016) “Narrative Discourse Intervention for School-Aged Children with Language Impairment”

This study introduced story grammar one by one in individual lessons highlighting the “causal connection that exists between them” when teaching them (“e.g., He ran because he was afraid the bear would eat him”).

📗 Hessling and Schulele (2020) “Individualized Narrative Intervention for School-Age Children With Specific Language Impairment”

This study used individualized sessions to target the story elements that students had difficulty with and paired them with coordinating elements. For example, if a student struggled with the “character” element, they paired it with feelings. After that, they would move on to another element after they were confident the student understood that element.

Now, on to how to shape narrative-based lessons for your students with SLI!

How do I scaffold the literacy-based therapy framework for my students?

Research has shown that you can teach story grammar before (Gillam & Gillam 2016) you start putting events together or during (Spencer & Petersen 2020). Use your clinical judgment to choose what works best for your caseload!

Gillam and Gillam (2016) outlined having students learn story grammar parts first before targeting retell with the story grammar elements. I tend to lean towards this method because students with SLI “often have deficits in auditory memory and verbal working memory” (Hessling & Schuele, 2020). During these sessions, you’re gauging and scaffolding supports for a student’s working memory and also adding extra vocabulary exposure.

How to Adjust Literacy-Based Therapy for SLI Students

➡️ Activate pre-story knowledge with what makes sense for your students. I use songs, videos, and play therapy. If we’re doing a book about penguins, we might watch a video about penguins as we describe them (pre-teach vocabulary), talk about what we already know, and act like penguins.

➡️ Next, you can make a decision here to teach story grammar first, or to teach it while you work on sequencing/retelling based on what works best for your caseload. If you are pre-teaching story grammar, complete that step before reading the story.

➡️ Do a book walk and make predictions based on the title and cover page. You can chart your predictions on a story grammar graphic organizer.

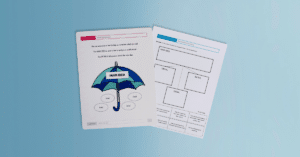

➡️ Use shared reading strategies and point out story grammar elements as you are reading. In later stages, you can have the students identify it using gestures or verbally (Spencer et. al., 2015). Then, have your students sequence/retell with the supports that work for your students (ex: acting it out, retelling with a story grammar visual). If your students need extra support, you can chart the story grammar elements while you are reading.

➡️. After you’re done reading you can go back to your story grammar graphic organizer and fill out more details. When you look at it from this perspective you can see how the supports that you put in place and then take away are working memory supports.

➡️ After reading the book and retelling the story, you can work on other goals like expanding sentences and describing.

➡️ Last but not least, create a parallel story giving as much support as needed for your students. If this is a difficult task for your students, you can create the parallel story together until your students can do this without support.

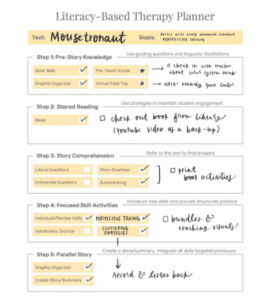

Here’s a link to a free literacy-based planner to help you plan and organize all of your activities!

What if my students aren’t ready to learn all of the story grammar elements?

You can adjust how many story grammar elements you teach.

Sometimes I may only start with 3-4 story grammar parts (character, problem, plan/attempt, solution/consequence) and build from there. Spencer & Petersen (2020) suggest that at a minimum episodes will include the “problem, attempt, and consequence”.

What if my students need support with temporal words?

After students are able to put 3-4 story grammar elements in order, I’ll switch to building up to using temporal words independently. I use lots of modeling and visuals!

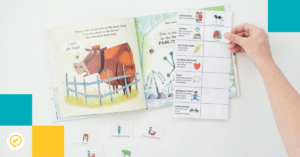

I adapt all of the SLP Now materials to fit my needs. There was a new update to include simple retell pictures and sentence icons so that you can support your whole caseload!

Here’s an example of how to do this with SLP Now materials. We will use Room on the Broom as our story.

✓Do any pre-story activities you want!

✓Go on a book walk and predict what might happen in the story.

✓You don’t have to read the story word for word! I may scaffold a story and just describe the pictures and what’s happening for some of my students.

✓After going on a book walk, we read the story.

✓For the retell we talk about how first there was a witch (the character).

✓Next, she flew into the sky (setting).

✓Then, she had lots of animals on her broomstick and it broke (problem).

✓Last, she made a new broomstick in a cauldron (plan/consequence).

Adjust the retell for how much support your students need. They may need you to just model it at first. You can use pictures from the SLP Now book activity for your retell (pictured below).

You can add support by using story grammar icons and placing them next to the coordinating picture (Spencer et al., 2014). You can do this while you’re reading or during your story retell. It’s a great way to get your students familiar with story grammar before they’re ready for it.

What about students that are working on WH questions?

You could also use the same worksheet to practice WH questions.

WHO: The witch is a character, and when we talk about WHO questions it’s the character.

WHEN: The night is the setting and that’s the answer to our WHEN questions.

WHERE: A broomstick is a place because she sat ON the broomstick and that’s the answer to our WHERE questions.

WHAT: At the end of the story, they make a new broomstick. That solved the problem and is the answer to our WHAT questions.

This is also a great time to talk about causal relationships between the story elements.

Here’s an example:

The broomstick broke (problem) BECAUSE there were too many animals on the broomstick, so the witch (character) had to make a new one (plan/consequence).

I like to highlight to parents and students that they need to remember all of the key details (story grammar elements) in their working memory to be able to answer WH questions. I tell students that’s why we pick out the important parts and put them in our memory to keep for later!

What about students that are working on expanding sentences and describing?

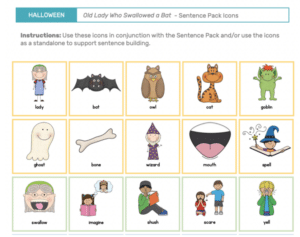

The book activity packets also contain icons that are great for students working on putting sentences together after retelling.

The icons also include describing words from the story. That’s a home run for mixed groups! I pair this sheet with the SLP Now Sentence Pack, a whiteboard, or sticky notes.

What about students that aren’t ready for the literacy-based therapy framework?

For students that I know won’t be able to start with picture books, I lean into supporting their vocabulary skills (learning about story grammar first) and work on creating a retelling schema to build up to working with the literacy-based framework.

This means that I want my students to know what story grammar elements are and be able to independently retell a simple story using pictures (basic episode). For students who are still working on putting words and sentences together, I adjust my visual supports. We’ll use core boards and sentence frames as needed.

When working on simple story retells, I will model the story first then turn over the pictures. I want my students to imagine what’s happening in their heads and then retell it to me using whatever mode of communication they prefer, using lots of verbal support. Later on, we might act out the story together. The last step would be to take the pictures away and have them retell the story independently. I use vocabulary like “character” and “setting” while I’m talking about the story, but don’t expect students to use the terms. That way we have lots of exposure to the story grammar elements before we even start going over them!

This progression is backed up by an article by Dempsey (2021), that showed that strong story comprehension skills were best predicted by a child being able to use a verbal account of a story (without pictures), followed by enactment (acting it out with prompts), then sequencing (retelling a story with pictures). This sets up a natural progression for fading support.

Another way you could adjust retelling for preschool students is using scaffolding, as outlined in an article by Spencer et al. (2014). These steps are for the retell phase. The article also outlines supports for a personal generation phase.

✓Model (show the pictures, model the story, put icons with coordinating picture, identify the story grammar parts)

✓Retell with pictures and icons (have pictures out for retell with icons, give support to the student with retell)

✓Retell with icons (take away pictures for retell, have icons out for visuals, support the student with retelling)

✓Retell without pictures and icons (no icons or pictures for retell, support student with retelling)

I hope that some of these strategies help you with your caseload and being able to provide literacy-based therapy! If it feels overwhelming, start small! You can start with a couple of groups to get the hang of it and expand from there.

Don’t forget that SLP Now members have access to The Academy which has lots of information about literacy-based therapy if you ever wanted an in-depth course!

References

Dempsey, L. (2021). Examining the validity of three methods of measuring pre-readers’ knowledge of storybook events. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(2), 137–148.

Gillam, S., & Gillam, R. (2016). Narrative Discourse Intervention for School-Aged Children With Language Impairment. Topics in Language Disorders, 36, 20–34.

Hessling, A., & Schuele, C. M. (2020). Individualized Narrative Intervention for School-Age Children With Specific Language Impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(3), 687–705.

Kamhi, A. G. (2014). Improving Clinical Practices for Children With Language and Learning Disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(2), 92–103.

Pico, D. L., Prahl, A. H., Biel, C. H., Peterson, A. K., Biel, E. J., Woods, C., & Contesse, V. (2021) A. Interventions Designed to Improve Narrative Language in School-Age Children: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analyses (world) [Review Article]. ASHA Wire; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Spencer, T., Petersen, D., Slocum, T., & Allen, M. (2014). Large group narrative intervention in Head Start preschools: Implications for response to intervention. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 13.

Spencer, T. D., & Petersen, D. B. (2020). Narrative Intervention: Principles to Practice. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(4), 1081–1096.

Ukrainetz, T. (2006). Contextualized language intervention: Scaffolding PreK–12 literacy achievement. Eau Claire, WI: Thinking Publications.

Reader Interactions