This is a guest blog post by Monica, a school-based SLP, is all about how to use semantic mapping & the research behind it!

Do you have students with word-finding difficulties, but are not sure where to start?

Have you talked to their parents and teachers and they really want their student or child to be able to expand on their ideas, but they really struggle with vocabulary? Do you wish you could embed another vocabulary intervention into your existing narrative therapy? Semantic mapping is here to make your life easier! Stay with me for how to follow EBP decision-making and to see if semantic mapping is a good fit for your students and their families. We’ll end with some therapy ideas for your sessions.

What is Semantic Mapping? How do you do it?

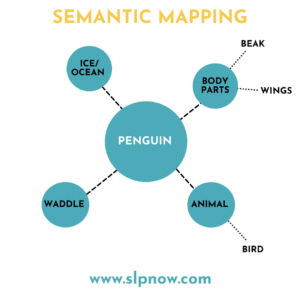

Semantic mapping is also called semantic feature analysis. We all know the term from grad school as a common form of therapy for aphasia. Semantic mapping is when you list out features related to a word. It is most commonly done using interconnected circles and charts. Using this strategy helps students/clients map out how words are related to each other and develop a deeper understanding beyond labeling (Alt et al 2004). Semantic mapping can include any words related to the target word to expand on knowledge about the target word. Examples of ways to expand on a word are: categories, physical attributes, actions, origin, emotions, and background knowledge.

What is Semantic Feature Analysis?

Semantic mapping has a lot of different names. In the research, it goes by semantic mapping and semantic feature analysis. We all know it from grad school because it’s a commonly used therapy approach for aphasia. What does the research look like for the preschool to adolescent population?

Preschool

Alt M, Plante E, Creusere M. (2004). Semantic features in fast-mapping: performance of preschoolers with specific language impairment versus preschoolers with normal language. Journal of Speech Lang Hearing Research. 407-20.

Preschool research for semantic mapping isn’t as easy to find. The research that is available points to SLI students having a more difficult time with semantic mapping than their peers.

The researchers suggested that these students are not just having a hard time labeling, but a deeper understanding of vocabulary.

Preschool students with SLI in this study had a more difficult time with actions than nouns.

School-Aged

Best W, Hughes LM, Masterson J, Thomas M, Fedor A, Roncoli S, Fern-Pollak L, Shepherd DL, Howard D, Shobbrook K, Kapikian A. (2018). Intervention for children with word-finding difficulties: a parallel-group randomised control trial. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 20(7), 708-719.

“Combining semantic intervention with phonological intervention led to on average 4x growth in the experimental group than the control group” (Best et al. 2018).

A randomized control study looked at word-finding therapy for children with language difficulties in a school setting.

Treatment was done once a week for six weeks individually.

Note: The children in this study scored within the normal range for comprehension and did not have a diagnosis of dyspraxia, autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, or global delay.

Adolescents

Lowe H, Henry L, Müller LM, Joffe VL (2018). Vocabulary intervention for adolescents with language disorder: a systematic review. Int Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 199-217.

Meta-analysis research for the adolescent population showed mixed results, but higher efficacy when using a phonological-semantic approach, with “outcomes that are better when the intervention is embedded in a wider language context such as a narrative approach.”

Overall, it looks like the research supports using semantic mapping when used hand in hand with phonological mapping. Embedding semantic-phonological mapping into a narrative approach may also improve outcomes.

Client/Student & Family Values

What are some things we can think about after we’ve selected a therapy approach to use?

Let’s look at how to incorporate the client/client’s family’s factors like values and cultural/socioeconomic factors. Consider the research when making a recommendation about service delivery to the family and making a team decision.

“Students who received services through a collaborative model had higher scores on curricular vocabulary tests than did students who received services through a classroom-based or pull-out model. Although all three services delivery models were effective for teaching vocabulary” (Thorneburg et al., 2000).

Clinical Judgement and Expertise

After you have decided that it is appropriate for your client and the client/family agrees that it is the best approach (maybe at an IEP meeting?), it’s time to use clinical judgment and expertise to think of the ways to best use this approach in therapy. Hang on tight, right after this, we’ll go over some therapy ideas!

Lowe et al. (2018) said that combining this approach with a phonological one and incorporating it in a narrative intervention has the most evidence behind it. Do you have students that would benefit from this approach? Semantic mapping lends itself to using a lot of visuals and is easy to adapt to different learning styles and support needs.

Set up a way to take baseline data and monitor progress (keep in touch with teacher/caregivers to see if it’s working).

We love working on areas that can give you more bang for your buck and have areas of overlap.

How is working on expanding vocabulary and strengthening this skill going to increase access to the curriculum and participation in the classroom for this student?

Will working on vocabulary and expanding those skills also help with socio-emotional skills for your student/client? Would this help conversational skills and general functional communication?

Last Stop: Therapy Ideas

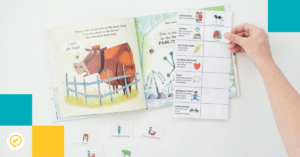

Use your existing narrative lesson

Incorporate semantic mapping by doing a book walk and map out new words before you start reading the book. You can also stop on ages to describe objects, characters, and setting using semantic mapping (e.g., what they look like, how they feel, and what they’re doing).

Make it functional

Pick places on their school campus or from home. Add sentence frames for extra support. Ask caregivers for ideas of things that they have a difficult time expanding on or things that they frequently have a hard time naming.

Collaborate

Work with teachers to do phonological-semantic mapping for upcoming themes and activities to increase participation in class. This would be a great time to incorporate actions as target items.

Use high-interest targets

Introduce new adjectives to talk about high-interest shows or movie clips to expand language.

Make a story with new words

Make a narrative or story using new words that you have targeted to increase word exposure. The more exposures to a new word, the better!

Don’t forget to use phonological mapping

Spell out the word and sound it out to include phonological mapping to help students learn the word. You can clap out the syllables, include a word that rhymes, or other words that start with the same sound.

But how do I know if it’s working?

Last but not least! Don’t forget to take the time to review if this approach is working by comparing it to that baseline data that you took. Best et al. (2018) showed that 6 weeks of intervention was needed to show a positive effect for vocabulary intervention.

References

Alt, M., Plante, E., & Creusere, M. (2004). Semantic Features in Fast-Mapping: Performance of Preschoolers with Specific Language Impairment Versus Preschoolers with Normal Language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research>, 47(2), 407-420.

Best, W., Hughes, L.M., Masterson, J., Thomas, M., Fedor, A., Roncoli, S., Fern-Pollak, L., Shepherd, D. L., Howard, D., Shobbrook, K., Kapikian, A. (2018). Intervention for children with word-finding difficulties: A parallel group randomised control trial. International Journal of Speech Lang Pathology. 20(7), 708-719.

Cirrin, F.M., & Gillam, R.B. (2008). Language intervention practices for school-age children with spoken language disorders: a systematic review. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 39(1), S110-37 .

Hadley, E. B., Dickinson, D. K., Hirsch-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2018). Building semantic networks: The impact of a vocabulary intervention on preschoolers’ depth of word knowledge. Reading Research Quarterly.

Lowe, H., Henry, L., Müller, L.‐M. and Joffe, V.L. (2018), Vocabulary intervention for adolescents with language disorder: a systematic review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53, 199-217.

Marulis, L. M., & Neuman, S. B. (2013). How Vocabulary Interventions Affect Young Children at Risk: A Meta-Analytic Review.Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 3, 223-262.

Throneburg, Calvert, Sturm, Paramboukas, & Paul (2000). A comparison of service delivery models: Effects on curricular vocabulary skills in the school setting. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9, 10–20.

Hi! I have a student who I know has word finding difficulties and would definitely benefit from this approach. I came across this blog post in search of how to get started to help him. I found exactly what I was looking for, so thank you!

My only question now is how to write a measurable goal to track his progress towards improved word-finding skills. Any suggestions?